Q1 2025 State of Venture Update

Tariffs, Tech, and Tactics: The Era of Strategic Competition with China

"I like China… People say, oh, you don't like China, no, I love them."

- Donald J. Trump

Excited to return to writing my updates after a brief, unannounced hiatus. This year's central theme appears to be China—in more dimensions than you might expect. Whether it's AI, biotech, academia, or tariffs, China is squarely in the spotlight. Even in defense, where 8VC has built a robust investment franchise, China remains at the forefront of everyone’s attention.

It’s not widely known, but I've been closely studying China since my days at Clarium, beginning in 2008. During that period, I immersed myself deeply in Chinese history, politics, and macroeconomic analysis, as I primarily covered the region for the fund. It wasn't unusual for me to stay awake until 1–2 AM trading Chinese markets, only to return to the desk in time for the 6:30 AM market open the next day!

It was a rewarding experience, and I've maintained my deep interest in the region ever since—leaving me reasonably well-qualified to comment on the current political and economic landscape. At that time, my view was that China would continue industrializing and emerge as a leading global power. Internally, this perspective was somewhat controversial due to the numerous risks facing the country, particularly the massive property bubble and rampant corruption at local government levels. Many believed such growth was unsustainable. However, I thought otherwise, primarily because of the enormous productivity gains from urbanization. When a Chinese farmer moved from a subsistence-level plot to factory employment, their productivity increased tenfold. Even if half of that gain was wasted, the net increase in prosperity would still be substantial.

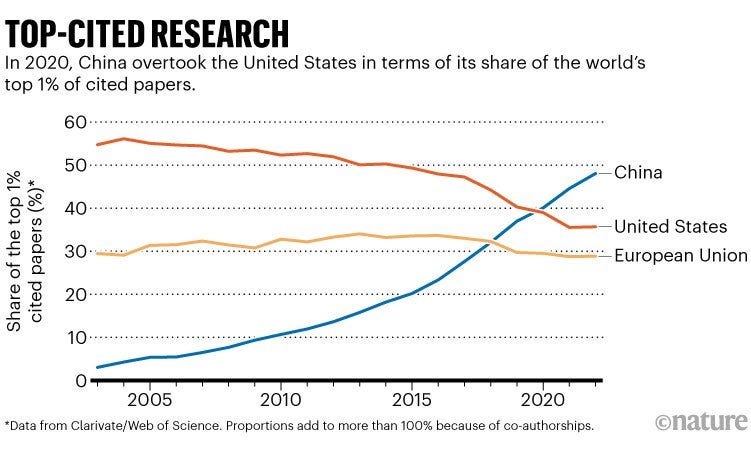

China has come a long way, transforming from the impoverished nation it was in 2008 into a global powerhouse. Back then, we used to say China advanced primarily by copying others—but today, China leads in many industries. A recent study by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute revealed that China now dominates global research in 57 out of 64 key technological fields, up from just three fields in 2007. Anyone working closely with China knows it's no longer merely a low-cost outsourcing destination; it now produces high-quality products across numerous sectors. Even in academia, Chinese research has surpassed the U.S. in terms of top citations.

And there's the rub: China initially competed through copying and intellectual property theft but has now, in some areas, surpassed the West in critical research. As China emerges as a potential peer adversary, its unique rise is causing concern in the corridors of power, prompting reactions from both government and industry. I'm not an extreme China hawk, but I do believe action is necessary given the trajectory we're observing—particularly regarding the intellectual property we've already lost.

Without further pontification, let me dive into what I believe this means for the economy and startups more broadly.

Macro Update & Tariffs - China Eats your Portfolio

In my view, the first major consequence of China’s rise manifests itself in our current trade debate. Driven by substantial trade deficits—most notably with China—policy tensions escalated dramatically on April 2nd when President Trump announced his "Liberation Day" tariffs on all countries, subsequently liberating Americans from about 15% of their wealth. Commentators debated whether Trump intended to free Americans from dependence on foreign nations or, in a more Buddhist sense, liberate us entirely from our material desires.

The administration has provided very little clarity regarding the intent of these tariffs. Ostensibly, they aim to reshore key industries such as energy, pharmaceuticals, and semiconductors—yet they've exempted precisely these sectors from the "liberation" tariffs. Statements from administration officials have been equally lacking in logical consistency. So far, I've heard three incompatible short-term outcomes promised (though the long-term message is clear: a golden age awaits):

There's nothing to worry about. Wall Street's rush to project lower growth is excessive. Everything will be fine in both the short and long term as we reshore industries.

It will be tough in the short term, but worth it. The tariffs will remain, eventually leading to an American economic boom as companies reshore.

We have more than 50 countries negotiating, and we'll ultimately reach a world of uniformly lower tariffs.

That leads me to a few conclusions with relatively high confidence. First, there is no master plan—the administration is simply reacting on the fly based on the circumstances presented to them. Whatever deal ultimately emerges will retroactively become the "plan." This explains erratic moves, such as implementing a 90-day tariff pause when markets crash, or constantly shifting exemptions. Second, anyone claiming to know exactly what will happen next is lying. We might soon witness a complete cessation of trade between the U.S. and China—or, alternatively, a swift deal could be reached. Similarly, global barriers might be reduced if countries cooperate to isolate China —or tariffs could persist indefinitely if they're deemed beneficial. Trust no analysis; the only prudent course is patience.

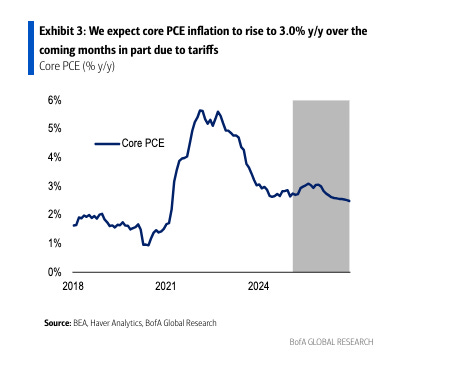

On interest rates, the administration's messaging is equally inconsistent. Trump clearly wants lower rates, yet both his tariff policies and his goal of reducing the trade deficit are likely to push rates higher. The tariffs themselves have a straightforward effect: they'll drive inflation upward—as Bank of America recently projected for year-end—and rising inflation inevitably leads to higher interest rates.

Reducing the trade deficit will also push interest rates higher, though the mechanism is less intuitive. The reason lies in the balance of payments. You've likely heard the claim that "China (or foreigners generally) finances our fiscal deficit." This is true due to the nature of the balance of payments, which must always balance: every dollar entering the U.S. must either purchase a good or an asset. I recently explained this on Twitter.

Without diving too deeply into economics, consider the current account (mostly the trade deficit) and the financial account (assets bought by foreigners). If the trade deficit shrinks, foreign purchases of U.S. assets decline correspondingly. This forces domestic investors to absorb more assets, driving interest rates higher (and prices lower).

Amid uncertainty, trade tensions, and rising volatility, the U.S. is trading like an emerging market. Typically, crises push stocks down and drive investors toward bonds and the dollar for safety. But with confidence in the dollar shaken and volatility driven by U.S. policy itself, we’re seeing stocks, bonds, and the dollar all falling simultaneously—reflecting capital flight rather than a flight to safety.

The conclusion of my macro update is that we genuinely don't know much. I'm confident inflation will stay elevated for now, and there's certainly recession risk. However, exactly where we'll land remains uncertain. If you're running a company, enjoy the ride!

ASIDE: I'm one of the few proponents you'll meet who supports targeted tariffs, but my frustration with the administration lies in their poor execution. A current account deficit is acceptable—we benefit from inexpensive foreign capital inflows. However, offshoring critical industries creates national security risks, and foreign trade barriers disadvantage American businesses. An effective policy would (1) identify and privately negotiate the removal of unfair barriers, using tariffs as leverage if needed; (2) strategically impose tariffs in sectors we want to reshore; and (3) implement these policies permanently, clearly, and with incentives, providing U.S. companies sufficient capital, certainty, and time to adapt. The administration falls short precisely on this third point, causing uncertainty and unnecessary financial burdens.

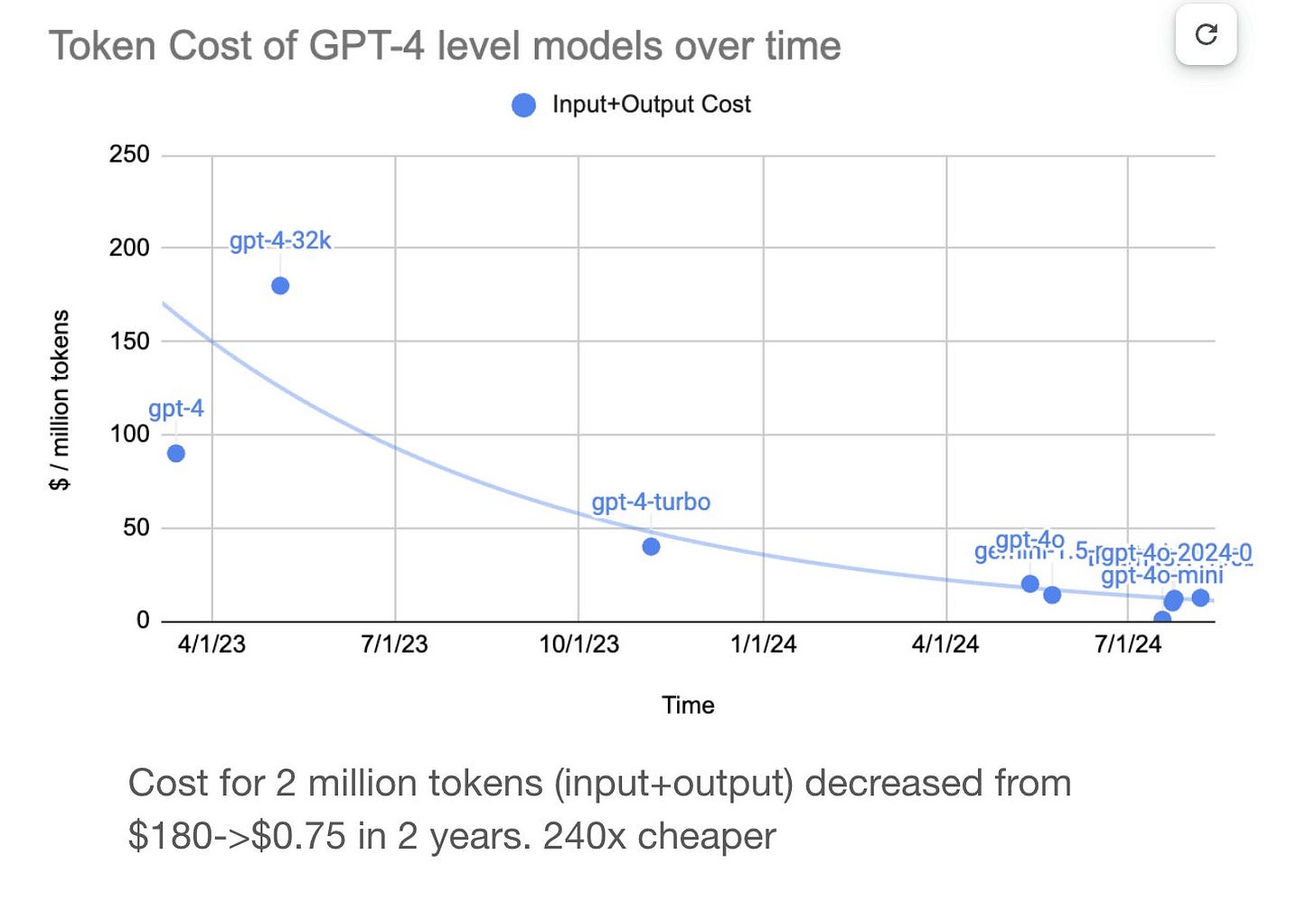

China Eats AI

China shocked the world in January with its release of R1, causing widespread panic. I found these reactions misguided (I'll aim to comment more promptly next time). Initially, there were fears that R1—open-source and near-frontier in capability—would commoditize AI, echoing the common adage that “when China enters an area, profits disappear.” But AI has been steadily commoditizing and becoming cheaper from the start; R1 hasn't materially altered that trajectory.

There was also concern about R1 being trained for only $6 million. However, this isn't the first time a lab has achieved near-frontier performance with less than $10 million. As I mentioned previously, Reka accomplished something similar—their core model reached #7 on LMSys. It's important to note that this $6 million figure covers only the direct cost of training, assuming the team already knows exactly how and what to train (as Reka did). It doesn't include the research costs needed to reach that point, which DeepSeek has not disclosed.

There was also considerable speculation claiming R1 had trained on outputs stolen from OpenAI. I'm skeptical of these claims, especially given DeepSeek's consistent track record of publishing high-quality research. It's not surprising that a team producing strong research would also deliver strong models; there's no reason to diminish their achievements. In fact, they introduced several impressive innovations, notably in wide MoE architectures, multi-latent attention, and low-precision training.

Ultimately, it wasn't the lower cost of training or inference that made R1 impressive. Instead, what genuinely surprised people was China's ability to release a near-frontier model—ranking #2 on LMSys at launch—despite extensive export restrictions. Yet even this shouldn't have been entirely unexpected; Alibaba’s Qwen models have consistently demonstrated strength, though R1 clearly exceeded them.

This fear has prompted the administration to enact further restrictions on GPU sales, including a ban on H20 exports and potential restrictions on DeepSeek—which, in my view, would violate the First Amendment.

The LLM model tier isn't the only area where China is competitive.

1) A Chinese company recently released a general AI agent called Manus, capable of using tools such as web browsers to perform various tasks. It's also notably proficient at code generation, and early reviews on Twitter have been quite positive. I haven't personally tested it yet—they're severely compute-constrained—but it's reportedly impressive. Benchmark recently invested at a $500M valuation [aside: I thought we weren't allowed to invest in Chinese companies anymore?].

2) In response to export restrictions, Huawei has made impressive strides in AI silicon development, recently introducing their own rack-scale AI architecture, the CloudMatrix 384, which directly competes with the GB200 NVL72. SemiAnalysis provided an excellent breakdown here. The TL;DR is that it's a strong product—less power-efficient than the GB200 but superior in some respects. While software gaps remain, especially regarding CUDA compatibility, it’s clear that China is actively advancing. This represents a significant threat to NVIDIA, considering China historically accounts for 20-25% of their revenue.

3) Alibaba released their frontier video-generation model, Wan 2.1. It's extremely impressive—on some benchmarks, it achieves frontier-level performance even compared to closed-source alternatives. Take a look at these examples here!

Are Chinese models near-frontier? In many cases, yes—most people likely can't distinguish state-of-the-art Chinese open models from leading closed-source US models. With Huawei’s CloudMatrix 384 release, a nationwide push to replicate the CUDA ecosystem is inevitable. Although this will take years, once China achieves it—and once SMIC can manufacture HBM—they'll have fully decoupled from the US in AI capabilities. This is why I believe NVIDIA’s GPU restrictions were premature. Limiting exports is a strategic move we can only use once, prompting China to rebuild their hardware and software stack. The optimal timing wasn't now, when AI's economic impact is still nascent, but rather in 3–4 years, when losing access to CUDA would truly hinder their progress.

So, will China ultimately win? No. GPU restrictions may not significantly impede their model training, but they will severely limit inference capabilities. We're already seeing this with DeepSeek and Manus—strong models with the applications made nearly unusable by compute constraints. As a result, China will likely focus on open-sourcing AI models, allowing others to provide inference hardware. This accelerates AI commoditization—a trend I've highlighted for years—standalone models remain weak businesses. Real value lies in the software and products built around these models, and historically, China hasn't excelled at application software. Build product!

China Eats Bio

In my view, the most concerning and immediate threat to America’s innovation economy comes from China’s activities in biotech. In this high-tech sector, China's competitive advantages and regulatory structure could effectively commoditize innovation. This presents a major challenge to U.S. biotech innovation and may pave the way for significant competition against U.S. pharmaceutical companies in the future.

Over the past decade, China has developed world-class capabilities in two critical areas of therapeutic development: medicinal chemistry and biologics discovery/manufacturing. In specialized niches such as bispecific antibodies, Chinese companies have become genuine global leaders—WuXi XDC, for example, is now the premier player in bispecific development.

But China hasn't limited itself to just providing services. Chinese companies now actively conduct clinical trials using infrastructure that's both rapid and cost-effective. They can run trials using non-GMP clinical materials, streamlined IRB approvals, expedited regulatory timelines, and recruitment from a significantly larger population. As of 2023, China accounted for 28% of global clinical trial initiations—a figure that's continuing to rise.

Now, more novel molecular entities originate from China than from Europe!

Now, here's the rub: The Chinese excel at rapidly and cost-effectively creating molecules and running clinical trials. They've combined these strengths with a fast-follower strategy in drug development. When a therapeutic target gains popularity in the U.S., often via biotech development, Chinese companies swiftly replicate it and advance it through Phase 1 trials—often faster than their U.S. counterparts. Afterwards, they typically seek to out-license these molecules to U.S. pharmaceutical companies at significantly lower prices.

This fast-follower strategy has enabled Chinese molecules to capture a substantial share of licensing activity. In 2024, molecules originating from China accounted for 28% of all licensing deals—a figure that has risen to 33% in 2025. Furthermore, nearly 30% of major pharmaceutical licensing deals (those exceeding $50 million upfront) involved Chinese biopharma companies in 2024, a notable increase from 20% in 2023 and virtually none five years ago!

These molecules aren't inferior or mere copycats—many represent genuine frontier innovations. For example, Carvykti, a BCMA-targeted cell therapy for multiple myeloma (MM), was licensed by J&J through a co-development deal with China's Legend Biotech and generated nearly $1 billion in sales for Legend in 2024. Fundamentally, Carvykti is Legend's drug, commercialized in partnership with J&J.

The surge in Chinese biotech activity poses an existential threat to the U.S. biotech industry. Chinese companies rapidly produce inexpensive fast-follower molecules, complete with Phase 1 data, and license them to U.S. pharma at a fraction of the cost U.S. biotechs typically demand. Given the high expenses of U.S. biotech research, this undercuts the value of original innovations. If this continues, it could severely impact biotech valuations, further challenging an industry where attractive returns are already scarce.

This doesn't apply equally across all areas of biotech. In fields with strong IP protection past composition of matter (bispecifics, TCRm and engineered TCRs), Chinese companies can't easily enter the U.S. market—but in areas without robust IP coverage, significant challenges emerge.

China Eats Defense & Industry

A silver lining of China's rise is that the potential threat of conflict in the South China Sea or elsewhere has spurred renewed innovation and readiness within U.S. defense, as I noted previously. The ongoing war in Ukraine has already highlighted critical vulnerabilities in America's defense supply chain—particularly regarding preparedness for a potential conflict with China, which we all hope never occurs. A recent report presented to Congress by the Commission on the National Defense Strategy concluded that "unclassified public wargames suggest that, in a conflict with China, the United States would largely exhaust its munitions inventories in as few as three to four weeks, with some crucial munitions (e.g., anti-ship missiles) lasting only a few days. Once expended, replacing these munitions would take years."

Among the commission's recommendations are proactive engagement with the private sector—particularly startups focused on emerging information technologies—to build a modernized industrial base. They also recommend reevaluating counterproductive regulations that currently hinder defense technology procurement and sales.

This geopolitical push, driven implicitly by China and Russia, has served as both a wake-up call and a boon to startups focused on defense and resilience.

Across the defense ecosystem, significant initiatives are underway to enhance capabilities on land, sea, and air, and to expand industrial capacity. Our company, Saronic, recently announced the Gulf Craft shipyard in Louisiana, which will build our new 150-foot Autonomous Surface Vessel (ASV), Marauder. We're bringing shipbuilding back to America.

Similarly, Anduril announced the opening of its Arsenal-1 hyperscale manufacturing facility in Ohio, designed to produce tens of thousands of autonomous weapon systems. This facility joins their solid rocket motor factory in Mississippi, robotic submarine facility in Rhode Island, and launched-effects factory in Georgia.

This aligns closely with lessons from the war in Ukraine, where drones reportedly cause up to 70% of battlefield fatalities, surpassing traditional munitions. Future wars will increasingly rely on drones and autonomous systems, posing significant threats to human combatants. Such a threat is concerning given China's dominance in the drone industry: Chinese companies control about 90% of the U.S. consumer drone market, 70% of the industrial market, and approximately 70% of global civil drone sales as of 2023. Continued reliance on drones in warfare makes this dominance a critical strategic risk.

U.S. companies are actively responding. Anduril has developed a comprehensive counter drone suite, while Epirus is focused on neutralizing drones using long-pulse, high-power microwaves. These companies are part of a rapidly growing ecosystem of businesses preparing to compete in the future of warfare. China's current dominance underscores significant opportunities for new U.S. entrants, particularly in technological innovation and industrial capacity.

Other supply-chain vulnerabilities are also emerging as critical concerns, creating opportunities for U.S. companies to reshore manufacturing. Any strategically important sector dominated by China poses potential risks. For example, during the pandemic, fears arose regarding U.S. access to life-saving medicines due to possible hoarding by countries like China. This concern motivated 8VC to found Resilience Bio, ensuring reliable, friend-shored manufacturing in this vital sector. Similar companies can and should be established in other critical areas.

Chinese involvement in these critical domains, from military threats to dominance in strategic industries, presents significant opportunities for U.S. startups. Countering these threats and reshoring essential industries will be major areas of opportunity over the next decade.

Conclusion

The point of my update isn't to suggest that all hope is lost. In fact, China faces significant long-term structural challenges of its own—inefficient governance, corruption, and demographic decline driven by poor top-down policies. However, the key takeaway is that China is a more formidable competitor than many realize, posing genuine strategic threats to American technological dominance. Moreover, any trade war with China carries the inherent risk that other global players might align themselves with Beijing, given its near-frontier technological ecosystem.

So what's the conclusion for startups? I think it's nuanced. Geopolitics isn't typically viewed as a major driver in private markets, largely due to their long investment horizons. However, I'd summarize the key takeaways as follows:

For biotech companies: China poses a significant threat. To succeed, stay lean, move quickly, and focus on frontier research protected by strong IP (some small molecules, bispecifics, TCRm, engineered TCRs, etc…).

For startups unaffected by tariffs: Stay focused and execute. Even during a recession, private markets likely have ample liquidity.

For startups impacted by tariffs: Adopt a wait-and-see approach—pause fundraising, conserve cash, and anticipate resolution within 8–12 weeks.

For defense and resiliency startups: BUILD!

My parting message for all Americans is to recognize the tremendous agency we have in countering the competitive threats we face. We don't need to rely solely on the government—except to ensure a level playing field. Rather than complaining that competition is unfair, let's simply get better.

Love this!! Would love your thoughts on some of my stuff, follow me back I could DM you?

Very interesting, thanks!

+ A top-down governing approach with the biggest population.